Five Words: Leadership, the UH-1 Air Ambulance, and the Transformation of Army Aeromedical Evacuation in the Vietnam War

By COL Donald E. Hall (Ret.)

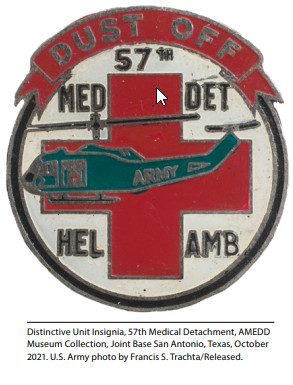

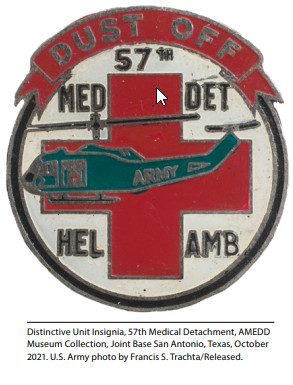

Army medical evacuation transformed on 1 July 1964 in a field South of Vihn Long in the Republic of Vietnam (Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, 2021a). MAJ Charles L. Kelly, commanding officer of the sole aeromedical evacuation unit in Vietnam—the 57th Medical Detachment (helicopter ambulance) headquartered in Saigon but operating out of Soc Trang with the unit’s Detachment A—is called to pick up a wounded American advisor.

Kelly leaves behind his flight medic and takes with him flight surgeon, CPT Henry M Giles, commander of the 134th Medical Detachment, the dispensary at Soc Trang. In those early days in Vietnam, the 57th took a flight surgeon along to care for wounded Americans, later dropping the practice when they determined that a flight surgeon couldn’t provide more care in the air than a well-trained flight medic could (Brady & Smith, 2010, p. 76). Kelly’s copilot, CPT Richard K. Anderson, and his crew chief, PFC Earl L. Pickstone, were also on board (Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, 2021a). Approaching the pick-up site, Kelly contacts the advisory team on the ground using his detachment’s well-known callsign, “Dustoff,” which in the Mekong Delta at that point in the war, was virtually associated with him personally. Kelly landed the aircraft (R. Anderson, personal communication, n.d.)1 and waited for the unit on the ground to bring out the casualties when he came under fire.

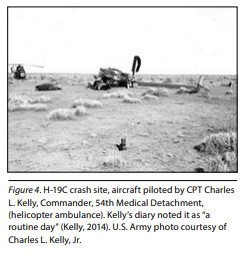

As his aircraft comes under heavy fire, the advisor on the ground tells Kelly to leave the area. The fire intensifies. The advisor on the ground continues to direct him to leave. Kelly calmly answers, by most accounts, “When I have your wounded” (Dorland & Nanney, 1982, p. 37; Cook, 1998, p. 67; Brady & Smith, 2010, p. 76). One account by Peter Arnett, who wrote what would become, in effect, Kelly’s obituary, recounts him saying “I’ll move when I have your wounded with me” (Arnett, 1964, p. 37). A single round enters the open left cargo door of the aircraft, pierces Kelly’s heart, and embeds itself in the aircraft frame to his right. He utters the phrase “my God,” and dies (Dorland & Nanney, 1982, p. 37), jerking back on the cyclic and up on the collective, which pitches the aircraft into the air and over onto its left side—striking the ground before Anderson can gain control of it—the rotor blades and transmission essentially destroying the aircraft (R. Anderson, personal communication, n.d.). Other accounts have stated that Kelly had the aircraft airborne when he was hit—CPT Giles recalls them as being at a high hover—about 30 feet in the air (Palmisano, 2011, p. 206). Still others have Kelly hovering the aircraft on the landing zone (Arnett, 1964, p. 37; Cook, 1998, pp. 66-67; TIME USA, LLC., 1964, p. 4). This was probably due to Kelly’s pitching the aircraft into the air when he was hit. Anderson kills the aircraft’s engine and fuel supply and drags Kelly from the wreckage. The rest of the crew help carry him to a nearby dike where Giles attempts to render aid, to no avail, while Anderson and Pickstone provide a defense (R. Anderson, personal communication, n.d.; Palmisano, 2011, pp. 206-207).

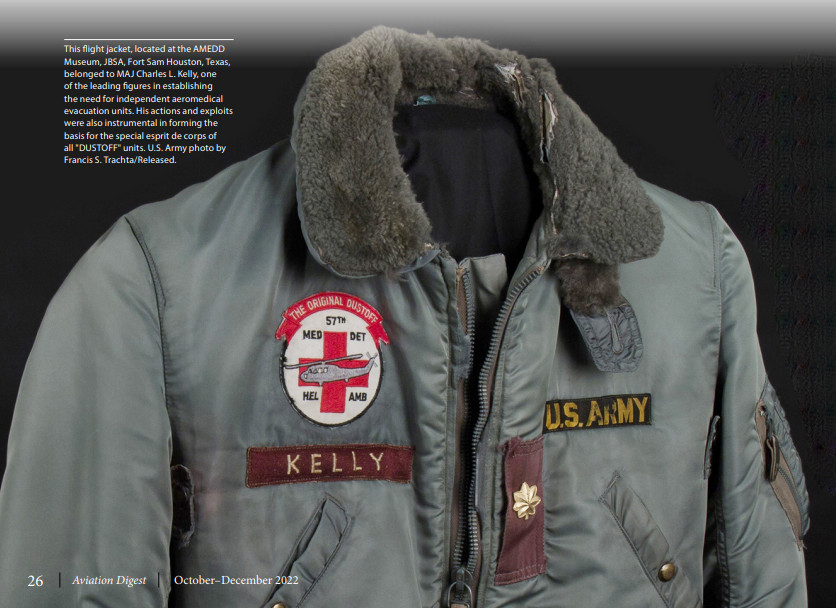

For his actions before the crash, Kelly would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, (Department of the Army, 1964), a Silver Star Medal for a mission in June, and the Distinguished Flying Cross with two bronze oak leaf clusters earned over a 5-day period in April (Department of the Army, 1964; Engert, 1966).3 Anderson, (Department of the Army, 1965b) Giles, (Department of the Army,1965a), and Pickstone (Department of the Army, 1965b) would each be awarded the Bronze Star Medal for Valor for their actions after the crash. Kelly’s death, coming as it did at a critical time in the fight over control of the medical evacuation mission, would settle the argument for the rest of the war (Cook, 198, pp. 68-69) and for the next 50 years. It earned Kelly the sobriquet “The Father of Dustoff” (Zabecki, 2018) (Figure 1).

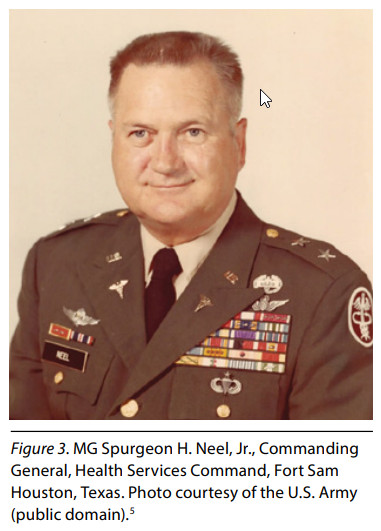

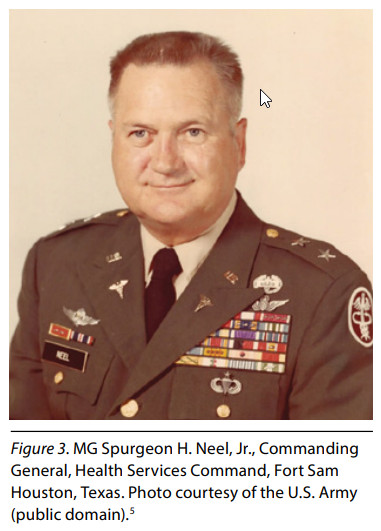

My thesis is that the Charles Kelly of legend is not the real Charles Kelly. While many of the stories are true or have their basis largely in truth, the real Charles Kelly had been leader developed (Department of the Army, 2022) throughout his career for his command of the 57th Medical Detachment at that point in time to settle this question: Is the medical evacuation mission a transportation mission that involves using helicopters to move patients or a medical mission that uses helicopters to accomplish its task? Further, he built his reputation using the most capable rotary-winged utility aircraft the Army had fielded to date—the UH-1 Iroquois—designed for use as an air ambulance (Dorland & Nanney, 1982, p. 19; Brown, 1995, pp. 102-105) and herded through the procurement process for the Army Surgeon General by Medical Corps LTC (later, MG) Spurgeon H. Neel, Jr., the “Father of Army Aviation Medicine” (Army Medical Department Center of History & Heritage, n.d.; San Antonio Express-News, 2003).

CPT Kelly was not only leader developed, he most capably led and taught others himself. A statement from his 1975 Army Aviation Hall of Fame Induction at Fort Rucker, Alabama, proclaimed “an exceptionally capable instructor in medical subjects as a Captain, Kelly demonstrated a high degree of positive leadership early in his career, an asset that became fully evident in later combat in Vietnam” (Army Aviation Association of America, 2020).

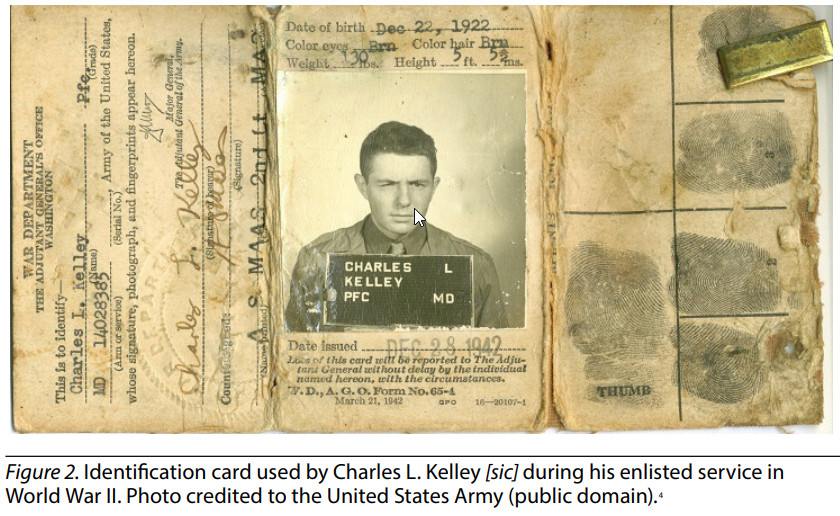

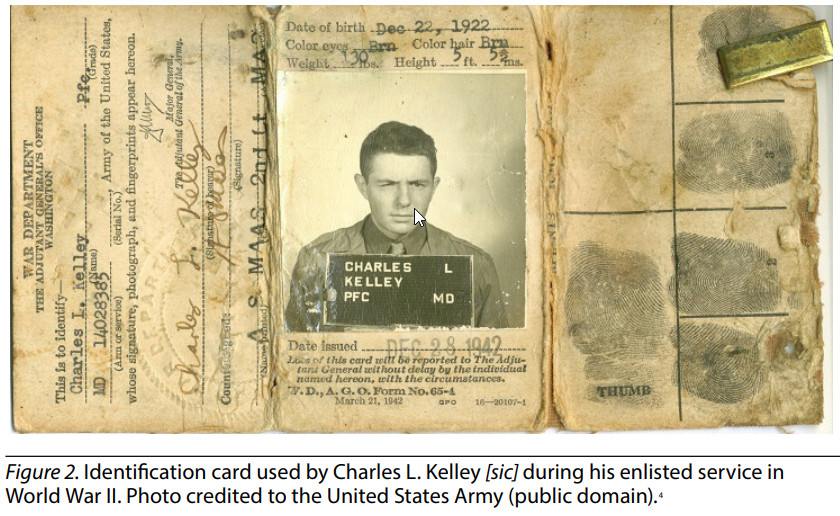

So, what do we know about Charles Kelly that led him to 1 July 1964? We know he dropped out of high school at age 15 to enlist in the Army at Fort Screven, Georgia, as a medic on 1 February 1941, using a variant spelling of his name and a false birthdate, (Fold3® by Ancestry®, 2012) and that he was seriously wounded during the battle for Aachen, Germany, while serving as an infantryman in the 30th Infantry Division (Clancey, 2022). For his service in the war, he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal, Purple Heart, Combat Infantryman Badge, and Combat Medical Badge (Military Hall of Honor, 2021; Hughes, 2022). Following the war, he returned to his home in Screven and completed his education, finally earning a Master of Science at the George Peabody College in Nashville, Tennessee (Engert, 1966) (Figure 2).

While Kelly taught for a short time, he also applied for a commission in the Army, was accessioned as a 2LT, and entered active duty in the Medical Service Corps on 25 October 1951. After completing his Officer Basic Course at the Medical Field Service School at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and the Basic Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia, he reported to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, for assignment to the 11th Airborne Division, serving in the 188th Airborne Infantry Regiment and 710th Tank Battalion (Engert, 1966). Kelly reported to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for class 54J of the Army Rotary Winged Aviator Course in March 1954, graduated, and was awarded his Army Aviator wings on 2 October 1954 (Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association, 2021b). He would then spend the rest of his career—and his life—on flight status, unusual for an Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Aviator.

Following graduation from the Officer Advanced Course, Kelly was assigned to the 55th Medical Group at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, as the group’s assistant operations and training officer and then moved to Fort Rucker and the Army Aviation School (Engert, 1966). There, he was assigned as an instructor in the school’s Air Mobility Branch, part of the Department of Tactics, as well as serving as the administrative officer to the Aviation Medical Advisor (Engert, 1966). His officer evaluation report (OER) from that assignment stated:

“Capt Kelly has demonstrated a remarkable ability to instruct in medical subjects. He is noted for his calm aplomb, exceptionally fine build, poise, and commanding voice on and off the instructional platform. He thinks very clearly, is alert to changes that will affect the instruction that is his responsibility, and Leadership and Leadership Development 23 possesses a high degree of common sense. One of his outstanding assets is his ability to organize instructional material well. Another of his assets is the strong initiative he displays in developing instructional material and in keeping abreast of current doctrine in the medical field. During the period he has served under me, he has proven to be an exceptionally capable administrator while acting in the capacity of a branch supervisor. He has also demonstrated a high degree of positive leadership in supervising the activities of several officers assigned to this branch. He is noted for his extreme devotion to duty and it has become evident that he is strongly motivated by a desire to perform better than his contemporaries. He is morally of strong character and is devoted to his family” (Engert, 1966).

Given the comments on initiative and keeping abreast of current Army aeromedical evacuation doctrine noted on Kelly’s evaluation, he probably came to know Spurgeon Neel during this assignment, as Neel was a vocal proponent of Army aeromedical evacuation. Neel published two papers on Army aeromedical evacuation while commanding the 30th Medical Group (now the 30th Medical Brigade) in Korea. From 1954 to 1957, Neel was assigned to the Office of the Surgeon General, where he established and served as the first chief of the Aviation Branch for the Plans and Operations Division of that office. There, he was responsible for all things related to Army aeromedical aviation. He published an article in Army magazine for line commanders on medical evacuation (Neel, 1956a) and co-authored an updated version of his 1954 paper on medical evacuation (Page & Neel, 1957). Additionally, he reinstated a program for placing Army flight surgeons on flying status that had ended when the Army Air Forces and their flight surgeons departed to become a separate service, as well as reintroducing the Army Flight Surgeon Badge (Neel, 1985).

Do we know if Kelly and Neel knew each other? Neel says they did. In a May 1974 article for the Army Aviation Digest, where he wrote of the accomplishments of Dustoff in Vietnam, he tells Kelly’s story and the story of Kelly’s greatest protégé, Patrick H. Brady. Brady flew with Kelly in the 57th as a CPT and would receive the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Service Cross as a Dustoff pilot on his second tour in Vietnam as a MAJ (he retired as an MG). Neel closes the article with “I knew them well and I am proud” (1974, p. 9) (Figure 3).

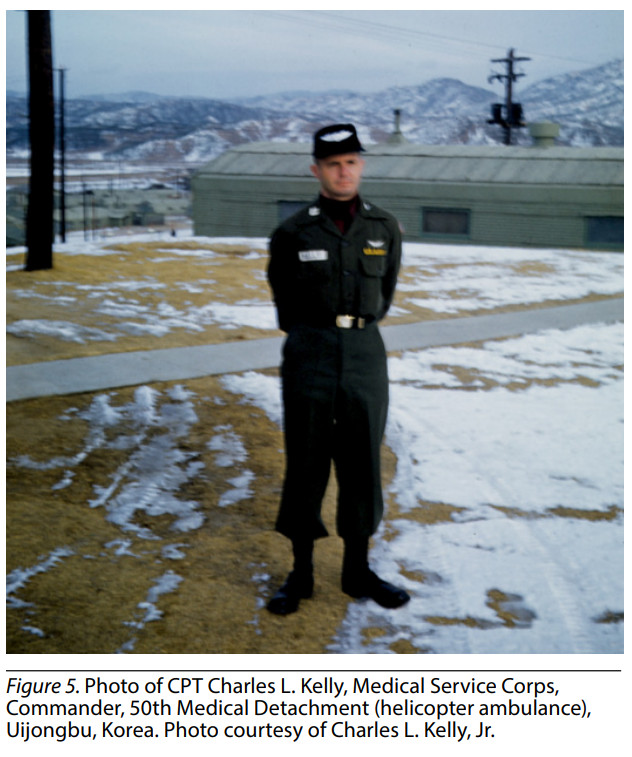

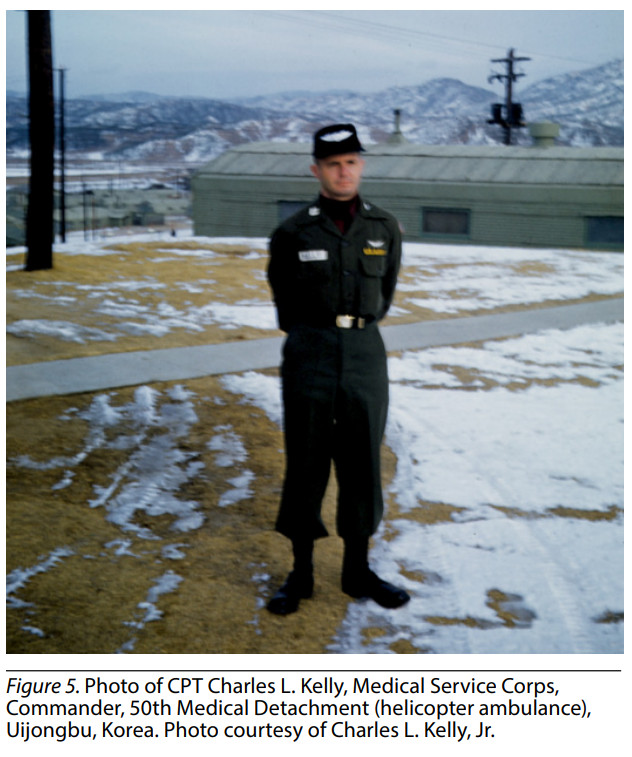

After leaving Fort Rucker, Kelly assumed command of the 50th Medical Detachment (helicopter ambulance) in Korea. The 50th Medical Detachment was located outside Uijongbu (Hough, 1999, p. 26), the same town near where the fictional 4077th M*A*S*H would later be reputed to be located (Hooker, 1997, p. 13). The detachment was known to have problems, and Kelly turned the detachment around during the year that he was in command (Figure 4). His OER contained glowing remarks about him as a person, pilot, and commander, and noted that “The morale of his personnel is outstanding” (Engert, 1966).

After completing his command in Korea and receiving an Army Commendation Medal at a time when peacetime awards of any kind were rare, Kelly was assigned to Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) at Fort Sam Houston (Engert, 1966).

In 1962, Kelly was assigned to Fort Benning as the commander of the 54th Medical Detachment (helicopter ambulance) (Figure 4). The 54th had been inactivated in Korea on 15 August 1962 and reactivated on 26 October 1962 under Kelly’s command as part of the buildup in support of a potential invasion of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis (Hough, 1999, p. 39).

Kelly left command of the 54th in December 1963 (Engert, 1966). He arrived in Vietnam to assume command of the 57th Medical Detachment (air ambulance) on 12 January 1964 (Christie, 1965). At that point, the detachment had been in country for nearly 2 years, arriving on 26 April 1962 from Fort Meade, Maryland, as one of the first AMEDD units to deploy to Vietnam, bringing with it the very first five UH-1s to arrive in-country (Conway, 1964). The 57th would also end up being the longest serving AMEDD unit in Vietnam, finally casing its guidon at Tan Son Nhut airbase on 9 March 1973 to depart for its new home at Fort Bragg 3 weeks before the final withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam—spending nearly 11 years in combat (Hueter, 1973). These five UH-1s led to a series of fights between the aviation community and the medical community over the role of the air ambulance for nearly 2 years. Was patient evacuation in Vietnam a transportation mission involving the movement of patients or a medical mission involving the use of aircraft—and did it require dedicated airframes or not? This was an issue that Neel had written extensively about during the 1950s, both in journal articles and policy statements for the Surgeon General (Neel, 1956b, 1956c, 1957). Kelly, as has been noted, knew both the aviation doctrine and the medical doctrine, and he knew it well. Thus, Kelly would be able to make arguments in favor of his—and AMEDD’s as an institution—positions that were hard for the aviators to argue against.

Did Kelly make doctrinal arguments to support his positions? The evidence indicates that he did in a 16 April 1964 letter to MAJ William R. Knowles, the Aviation Advisor in the Office of the Army Surgeon General. Kelly wrote: “I have won all the arguments so far. … But I can’t just tell them no. … Just get me the right regulations to back up the doctrine of the Army Medical Service. And don’t quote me the regulations, send them to me. It is hard to get them over here” (Kelly, 1964a).

Further, Kelly continued his aggressive piloting and fierce loyalty to his organization and men, just as he had in his previous commands. Kelly’s unstated command philosophy—often attributed to him and reflective of his nature but according to Pat Brady, was never actually voiced in Vietnam—was “No compromise. No rationalization. No hesitation. Fly the mission. Now!” (Gill, 2017). That also made it hard for the aviation community to argue against

Kelly, for he not only talked the talk he walked the walk. Indeed, in the OER that he received in April 1964, his rating officer, Artillery COL Raymond R. Evers, who served as the U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam Chief of Staff, noted that:

“Major Kelly has provided mature leadership to his unit in combat, gaining the respect and admiration of his associates and the loyalty of his subordinates. He is outspoken and has strong feelings on most any subject which involves the mission or welfare of his unit. He has been eager to serve the medical evacuation needs of the command and willing to take whatever personal risks were necessary to assure the welfare of the patients entrusted to him … His unit enjoys an excellent reputation among other aviation units. His unit never refuses a mission night or day for support of ARVN or U.S. troops” (Engert, 1966) (Figure 5)

In an OER dated 30 June 1964—likely the closeout after his death—his reviewing officer, COL Klingenhagen, an infantryman and Army Aviator who was the Deputy Commander of the U.S. Army Support Command, Vietnam, wrote:

“I personally observed Major Kelly on many combat operations. He is one of the most aggressive commanders in Vietnam and his unit reflects his dynamic leadership by always accomplishing their mission even under the most hazardous of conditions … Major Kelly has done an exceptional job with his unit since taking command. His unit’s discipline and appearance have improved materially” (Engert, 1966).

In his April 1964 letter to Major Knowles, the same one in which he asked for copies of doctrinal publications and regulations, Kelly wrote, while discussing his next assignment, that he intended to retire shortly after returning from Vietnam (Kelly, 1964a). Two weeks before he died, in another letter to Knowles, after again discussing the issues that the 57th was facing and how he was dealing with them, he closed his letter by stating:

“Don’t forget that I am going to retire. Don’t go to the trouble of answering this letter for I know that you are very busy. Anyhow, everything has been said. I will do my best, and please remember Army Medical Evacuation FIRST” (Kelly, 1964b).

The truth is that Kelly did not have to attempt that landing. Nor did he have to remain, waiting for his patients under enemy fire. The advisors on the ground told him to leave. But that wasn’t Kelly’s way. Patrick Brady, not one to shy away from danger himself, called Kelly “the greatest individual soldier I ever knew” (American Veteran’s Center, 2021). And in a McCall’s Magazine 1966 anthology, “The Gift of Love,” GEN William C. Westmoreland chose Kelly as an example of “the greatness of the human spirit,” and said of Kelly:

“The Major Kellys … have given America more than they have taken from her. And they are still giving, for when the going gets rough and an extra ounce of effort is needed, Major Kelly’s last words still shine brightly: “When I have your wounded” (Westmoreland, “General William C. Westmoreland, Commander, U.S. Forces in Vietnam,” 1966).

If Kelly had turned away from that landing zone or left when directed by the advisors on the ground, no one would have said anything about it, and it was accepted practice in the Korean War (Blumenson, 1987, 1990, pp. 111- 112). Indeed, after Kelly’s crash, another Dustoff aircraft piloted by Brady and 1LT Ernie Sylvester went into the landing zone and made the pickup later that same day—Kelly’s bird still a mangled heap nearby (Brady & Smith, 2010, p. 77). But Kelly would not do that. Nor would his men. Nor would the men who followed them. Nor the women who joined them. And that is both Kelly and Neel’s transformative legacy. Because Neel saw the air ambulance not just as a transportation means but as an asset where care could be given en route, and Kelly knew that the only way to make use of that asset properly was to bring it to the point of injury— regardless of conditions in the air or on the ground—and then bring the patient directly to the point where the most appropriate care could be given. This, in turn, allowed the hospitals in Vietnam, no longer required to relocate frequently on the battlefield, to become semi-permanent facilities with equipment, and in some cases rivaling that found in stateside hospitals (Neel, 1973, pp. 59-60). And this is why Kelly’s declaration, “When I have your wounded” are the five most transformative words in Army medical evacuation.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to thank the assistance, advice, and encouragement of Mr. Charles L. Kelly, Jr.; MG Patrick H. Brady (Ret.); Dr. Dale C. Smith, PhD, Professor and Chair Emeritus, Section of Medical History, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; and Dr. Michael Doidge, PhD, contract historian, Vietnam War 50th Anniversary Commemoration Commission.

Biography: Retired Army COL, Donald E. Hall, PhD, is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Military Medicine and History at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and is the Assistant Director of Staff at the Defense Health Agency. He is a qualified Army Pathfinder and former Chief of Staff of the 44th Medical Brigade.